Snowden: One quick technical question: I'm not sure how you're recording your audio, but I see there is another session, there's someone else connected to this room. If you look on the right-hand side of the screen, there's a session with no camera, no microphone activated, and it's just a light. So that's not yours? That's not from your technical room? There's someone else, we don't know who it is.

Stefan Koldehoff: We built up a second way just in case it wouldn't work. So we have the first line, but we have a second line from a laptop as well. Do you feel better –

Snowden: That's fine!

Koldehoff: – if we close that one or is that okay?

Snowden: No, no, not at all. It's just, yesterday I was doing one of these and I saw this, and it wasn't from the technician. So as long as it is from you, that's fine.

Koldehoff: Mister Snowden, thank you very much for taking the time. How can we be sure that we're really talking to Edward Snowden? There are fake videos, there are fake audios. Is there any proof that it's really you?

"One of the central questions that the world faces today: what can we trust?"

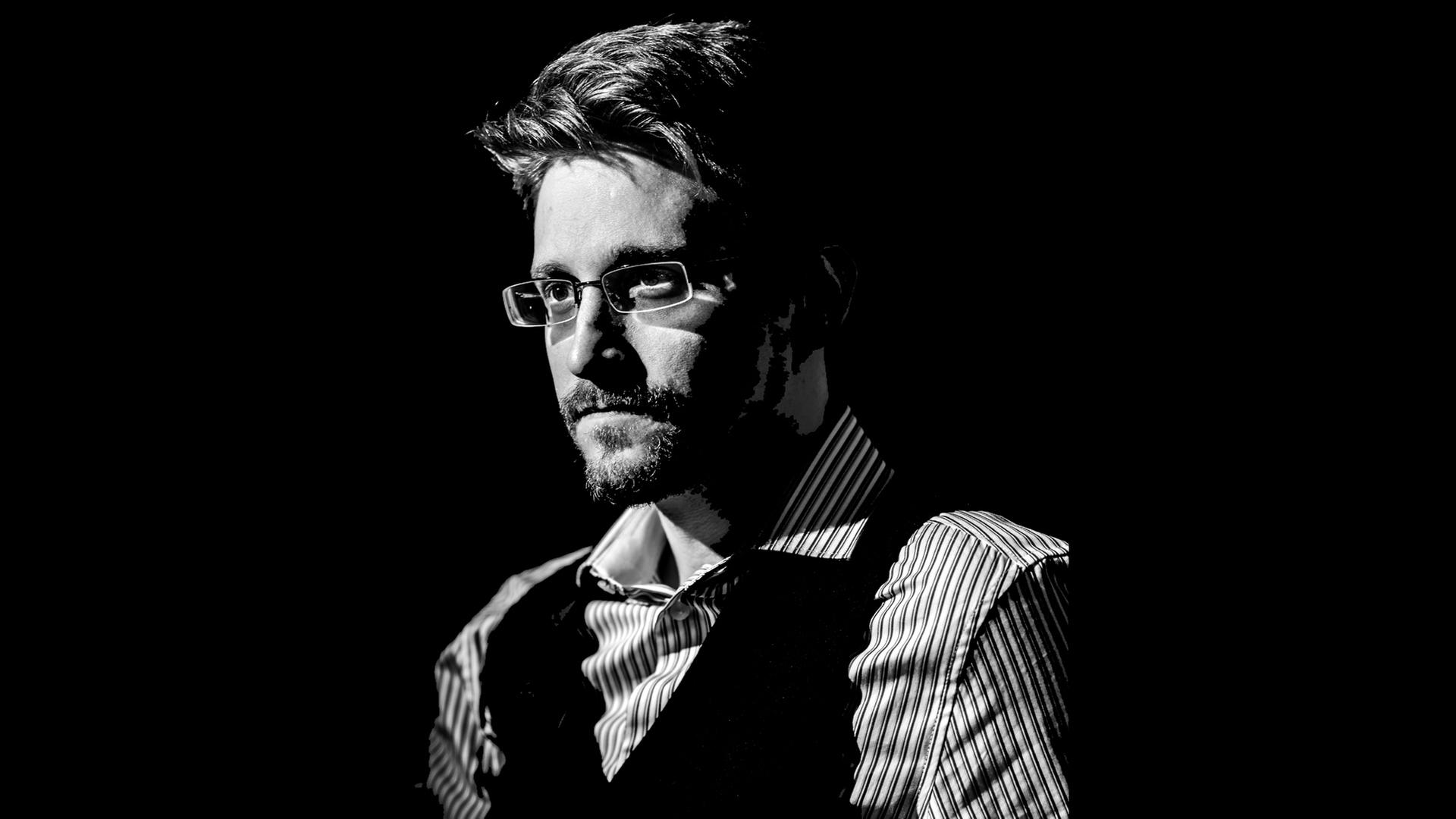

Snowden: Well, you know, this is one of the central questions that the world faces today is what can we trust, how do we establish authenticity, authenticity of documents, authenticity of claims, authenticity of ourselves. I think, one of the things that made what happened in 2013 so strong was, these were not arguments or claims or anything that was coming from an individual, although I'm very much associated with the revelations of 2013.

These were documents from the government itself, what they said internally, what they said privately behind closed doors that they deny the public the knowledge and access to. It was only when the government really acknowledged these were legitimate, they never questioned the authenticity. In fact, they confirmed that by charging me with crimes for telling journalists that these documents existed that we got some indication of authenticity. So in the case of this conversation that we're having right now, you can see me live, and fortunately I don't think we have the ability to do deep fake video live yet. That has to be rendered frame by frame by a form. You also spoke with my associates, the people that I trust, my publishers, my lawyers, my agent.

"I have not defected, I have not changed my loyalty"

Koldehoff: Are we allowed to know where you are exactly at that moment or do you prefer to disclose such details of your life?

Snowden: I'm in my apartment in Moscow that I rent myself. I mean, this is a great question, because people have, I think, well, at least there is some conspiracy theorists out there who think that I'm living in a bunker, you know, buried under a missile silo, behind armed guards, that I'm living under an assumed name. The reality is I'm not. In 2013 I was much more careful, but I never had guards. I have been on my own because I have refused cooperation with any government. I have not defected, I have not changed my loyalty. My loyalty was and is today to the American people. But this is something that's important for us to remember, and I think one of the challenges of our time, particularly in this new era of, shall we say rising appetite amongst governments to trend toward something close to totalitarianism. This is that when we talk about patriotism and what that really means, there are so many who confuse it with nationalism. There are so many who confuse it with the destruction of a foreign rival or a domestic opponent, a different group, but this is not what patriotism really is about. It's not about love of country. That confuses what patriotism is about. Patriotism is not about love of government, it's not about love of faction, it's about love of your people. It's about love of the country, it's about community. This is, when you ask about what I do, where I live, I more than anything else live on the internet today, but my allegiance will always be with my people.

Koldehoff: Our technician just tells us in this very moment that the second participant is not our laptop.

Snowden: Okay! We can fix this very quickly.

At this point Deutschlandfunk disconnects and establishs a new connection.

Snowden: Okay, so I'm sorry about that. That was very unusual. That's only begun in the last few days.

"I’ve seen surveillance challenges over the years"

Fries: So you don’t experience something like that frequently, only since you begun starting doing interviews?

Snowden: Yes, on this system. Of course, I’ve seen surveillance challenges over the years, but this one is unusual, because it’s, as you saw, so obvious. You have a third party connected to the room that we’re talking in, we’re holding an interview in, and they just have no microphone, no video enabled, so we can see or hear them, but they can still see or hear us. It’s very unusual.

Fries: But are you under some kind of surveillance that you are not able or that you maybe are able to guess, there is some kind of surveillance but you can’t really recognize, notice?

Snowden: Well, in terms of in my life I’m sure I’m targeted by every major intelligence service, because they’re always going to be interested in my activities, what intelligence services call someone’s plans and intentions. It’s typical for them to write reports on this for basically anyone of interest who comments on or reports and investigates the activities of intelligence services, because they see the public awareness of their activities or the public oversight of their activities as a threat.

Fries: So how do you deal with it?

Snowden: Well, what you can do is you can try to do what anyone would do, and this is use devices that are a little bit more secure, use methods of communication that are more secure. Things like end-to-end encryption, you never send anything over the open internet unencrypted. You use something like the torrent network, you never use SMS or normal voice call that is unencrypted, unprotected on your phone, because these transit the path, the path of communications whether you’re going over any medium electronically naked, unencrypted. Every communication that happens today, it is quite feasible to do this in encrypted form. Things like e-mail, for example, e-mail should no longer be used. We have alternatives that are more secure and more private. So it’s really a question of why anyone is using e-mail at all at this point when we have so many more secure alternatives.

Koldehoff: We’ll talk about that later about encryption and things like that, I’m sure. This interview has a reason. You’re publishing a book which will come out next Tuesday. What other reasons do you have to go to public, how do you decide whether to respond to a question, to give an interview or take part in a conference? What are your criteria for that?

Snowden: Primarily it’s just, does it serve the public interest. I try not to speak if it is going to be a distraction from the things that actually matter. This is why in 2013 when everyone in the world was trying to interview me I gave no interviews for six months. I came forward in June of 2013 and that’s when everyone saw the very first time I spoke, and then I had no interaction until the reform effort that really gotten off the ground. The reason for this specifically is if I had come forward and been on the news every day, it would have been even easier for governments to say, hey, let’s not talk about surveillance, let’s not talk about the ways we’ve been breaking the law, let’s not talk about violations of human rights. Let’s talk about this person. Aren’t they strange, aren’t they unusual, you know, isn’t there something we shouldn’t like about this person. Or maybe there is something we should like about this person. This is the thing with every, IC propaganda effort whether it comes from governments or whether it comes from corporations. If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about the answers.

"I use my story to tell what is actually a dual history"

Fries: But already in 2013 you said, I’m not the story. Now you wrote a book about yourself. Now you are the story of this book. Why did you change your mind?

Snowden: It’s not exclusively about myself. That’s actually something I think that is quite central to why this book is special. Yes, of course, it tells the story of myself and that’s because everyone, including you fine gentlemen, that I’ve spoken with in media, they say, you need characters to get the public to pay attention to a story. Fortunately, there are people who are still interested in this story and in my story. So what I do is I use my story to tell what is actually a dual history. Yes, the history of a person, yes, the history of a boy becoming a man, but also the history of a time, a moment, a change, the changing of the early internet from a place that is cooperative and creative to what we have today which is commercial and competitive, the change of the intelligence services that I came to work for in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks, and, really, I would argue, the decline of the American government’s sort of core professed values, from a structure that was entirely designed around the idea of targeted surveillance: We know this person is a criminal, we believe this person is a spy, and so we collect their communications, we spy on this building, this company, this embassy, not an entire country, not our entire population. But in the wake of September 11 and the real panic, the fear that ensued and to this day, unfortunately, still hasn’t evaporated. Governments, not just my government, but many governments around the world have begun to abandon those values of restraint and really protecting and also projecting the idea of a liberal, free and open society and replacing it with this thing of, this system of control. When we’re talking about surveillance, what surveillance is about, surveillance is not now nor has it ever been about public safety. It’s about power, it’s about control, it’s about influence, it’s the ability to predict and to shape outcomes. This change from targeted surveillance to what the government calls bulk collection, which is a euphemism for mass surveillance, is really, I think, the most important change in historic terms in the work of intelligence in my lifetime.

Koldehoff: Would all this have happened without September 11 2001 as well? Could it have been just out of technical abilities that a system like that could have developed either?

Snowden: That’s a difficult question but an interesting one. I think there would have certainly been pressures to do this. In fact, we know that in my country the government had already proposed these kind of programs internally and circulated them. The famous Patriot Act or rather infamous Patriot Act was already written before the attacks that happened on nine-eleven. The problem for the government was, they didn’t believe they could get the support of the legislature to pass it, because it was too extreme, it was too invasive. So, yes, there were always designs to get these capabilities, but there is a question of: without a moment of truly national trauma, without that moment of crisis, could the government actually have succeeded in at least attempting to legalize the expression of these authorities, and I’m not sure that’s the case. I think, when we see these truly structural changes to the way a government works it is often opportunistic. It is responsive to a public fear which the government itself has stoked to a great extent to then capitalize on and expand their mandate.

"I’ve been writing for six years"

Koldehoff: Let’s come to your book. You gave away all information you had before entering the plane that brought you to Moscow where you stranded, you wanted to go to Ecuador. You gave all information to the journalists, asked them to publish them and, well, erased your hard discs, destroyed them physically. Nevertheless, there’s a lot of detailed information in the book about certain things that happened, certain people you met, certain structures, you must have a great memory. Do you?

Snowden: Well, I’ve been writing for six years. I just haven’t been writing in the form of a book for that long. I have been talking and thinking about these topics to make my living until we’ve gotten to this point. So, yes, of course, I’ve had quite a number of notes about what’s going on, but that’s not about sort of unpublished classified information. That’s just the story of what is happening in the world, matters of public importance and of personal memory.

"They’re constantly creating new methods of surveillance"

Koldehoff: Do you think you’re still up do date concerning the activities of the intelligence community, the NSA? Are you still able to read data, to talk to people or is that no longer possible?

Snowden: I can’t talk about who I am or am not talking to in the United States intelligence services, because that would obviously be tremendously risky for them and their career. But what I can say is this: The programs always change, constantly change. The capabilities are always, some are being destroyed, some are being created, because that is what an intelligence service does. And by the way, intelligence service is very much trying to encourage a way of thinking about them is like a warehouse of gadgets, and if someone tells a journalist about this gadget or that gadget, that gadget is no longer effective. The reality is, they’re a gadget factory. They’re constantly creating new methods of surveillance, and old ones are becoming less effective.

But while the programs do change over time, the principles are always the same. This is really a large part of what the book is about is how I came to understand that many of the points in my career that would seem to be not so interesting, for example the creation of a new kind of backup system, so if the agency loses a site in a fire or an attack no data is lost, how that’s actually part of a larger system. When you understand the big picture of what’s happening, when you understand how all the individual gears interlock to create a larger machine, that is what is a constant, because there are certain things, only so many ways that we can be monitored. The fundamental basis of all of this is, every communication, no matter how it is transmitted, has an origin and a destination, there is somewhere it came from and there is somewhere it is received. If you can insert yourself between this path you can try to collect it. The only way around that is to try to encrypt it. Even with that there’s things like metadata which we can talk about later. Increasingly there are other methods.

"You can ask the telecommunications provider to save you a copy"

So if we can go into a little thing, if you want the technical explanation: For example, the status quo today, if any government or corporation or criminal group wants to spy on a communication, they want to get a copy of a message. There are only a few places they can get it. The easiest, the cheapest and the most common, since at least in the framework of modern history, is along the path, as it transits the internet or as it transits our phone network, if it is unencrypted or electronically naked, as we discussed before, you can simply be on this path. You can ask the telecommunications provider to save you a copy. You can be on the same wireless network sitting in a Starbucks and intercept that copy. If you encrypt it, you remove the ability to read the contents in this communication, but you can still see that the communication passed by, because it has to have some routing information. Think about sending a letter in the mail. You can put it in an envelope, but you have to write on it, send it to this person so that someone can actually deliver it there. So there’s the path. You also have the endpoints of the communication, and this is increasingly where we see forces hostile to the public focusing their interests and activity today.

"They could also go after the person that you’re talking to"

This would be, for example, your cellphone. If they wanted to hack it, let’s say, you encrypt all your communications, they can’t read them on the path, they go, well, if we hack into your phone, we don’t need to break the encryption, because we can simply steal the key to those encrypted messages that has to be on your phone in order for you to be able to read these messages, to be able to decipher these messages. They could also go after the person that you’re talking to. Let’s say you are very good at security, but the person you’re talking to is not, because every communication has a source and a destination. These are the two points they could go after. Then finally, the third part, we have the transit path, we have the endpoints and then we have the middlemen. This is Google, this is Facebook, this is Amazon, this is Apple, this is Microsoft, all of these cloud-service providers where they don’t actually allow you to send a communication on their services in many cases that just goes to the person you’re talking to. Instead they want you to keep a copy of the communication that you’ve given to them, that you backed up to their service, that you put on Facebook, that they can read, they can analyze, they can create records of your movements, your activities.

"It is fundamentally a dangerous power to trust to anyone"

Your contact list is one of the first things that when you install an app like Facebook, it does, it just ransacks your phone for anything that looks like an address book so they can fill out their understanding of how everyone in the world is connected to one another. So we see governments increasingly going, well, why don’t we simply coerce or seduce these companies into working for us, into sharing information with us or to actually redesign their service to be more accommodating to us to weaken our encryption. And basically they transform companies into kind of deputies, like little sheriffs. The interesting thing, when you talk about this in an international context, because the majority of all the world’s internet giants are located in the United States, they’re not really deputies of the German government, they’re deputies of the American government, and unfortunately this means there are unequal legal standards. If you’re German and the United States government wants to read anything in your Gmail-box they don’t need to go to a judge and get an individualized warrant for that, because they have a broad warrant for foreign intelligence that doesn’t have any names on it because it doesn’t need them. They can simply go under this authority, we’re going to demand Google hand over everything that you have ever typed into a Google search box, everything that’s ever been in your Gmail-account, doesn’t matter whether you’ve deleted it or not, everywhere your phone has ever been, everything that you’ve ever typed into Google Maps, really everything that they have. This happens secretly. I would say that is fundamentally a dangerous power to trust to anyone, much less a government that – while it traditionally has been and we would like to believe it is one of the defenders of the liberal tradition – today is in a real moment of historical trouble internally.

"They made the law follow the intelligence services"

Fries: So did things got worse since your revelations in 2013?

Snowden: Yes and no. There is a lot of nuance. The question is: get worse where, get worse how. When you look in the context of Germany for example, you’ve seen the BND scandals, you’ve seen the German government at the same time they’ve been complaining about surveillance by other states, they have actually been expanding and conceiving their own efforts of mass surveillance while denying that it’s mass surveillance and using different terms. It is this redefinition of language, this is really a problem in every country. I don’t want to pick on the German intelligence agencies. This is not about the BND. It happened in France where we have the laws. It happened in the UK where we have the most extreme mass surveillance laws that have been passed really in any western democracy at the time they were passed until they were very quickly one-upped by Australia. We’ve seen the same thing happen in Canada. Whereas in the United States we actually saw some reform, the most significant intelligence reform since the 1970s. The sad reality is, the most significant intelligence reform since the 1970s means: not very much. We did have the ending of one program where the government itself was adjusting all of these records, but Obama in response to the scandal passed a new law which created a new paradigm where the government would no longer hold these records itself, but it would simply deputize the telephone companies, as we’ve discussed before, to hold this records for the government, and the government would then ask them to respond to these things. So, yes, when we talk politically, there has been a backslide. When we talk strictly about the regulation of intelligence services – and this is for one reason and this is why 2013 was so important, I believe –, many of the most advanced countries in the world had abandoned their belief in this idea of enumerated powers, in this idea of monitoring only those who are suspected of a crime.

They were all building and cooperating in these systems of mass surveillance that allowed them to monitor the communications of everyone regardless of whether they were criminal or not, because technology made it possible and because secrecy made it politically available they pursue these systems. Now in the wake of scandals all of these people in governments who knew about these programs, who had denied their existence to the public and now suddenly these people, their reputations, their positions, their legacies are on the line. So what do they do? They do something that is sadly quite typical in response to scandal, which is not to reform the activities of the people who had been violating the law, but rather to reform the law to conform with the activities of the people who had been violating, rather than making the intelligence services follow the law, they made the law follow the intelligence services. But even with this all, all was not negative.

"Even if you live in Germany your data lives all over the world"

We did get out of Europe the GDPR, which is, I think, a very significant step forward, because it’s the first time we have seen even a meaningful appetite on the part of a major global player to try to change this regime. The GDPR is not enough, the GDPR in many ways is quite parochial, it presumes that you are an individual nationality, and your data subject can be the same thing, but even if you live in Germany your data lives all over the world, it lives in Maryland, it lives in Silicon Valley, it lives in India, it lives in China, it lives in Russia until the data protection commissioners in Europe are actually willing to apply those four percent of global revenue fines to Facebook and Google every year on a continuing basis, until they reform their activities. And now the world’s companies realize, oh, this is serious. The law won’t actually achieve any meaningful reform. I mean, it has to have teeth, and so far they’re still treating these companies as partners rather than threats. There is one last problem in this before I stop on this subject. Well, actually two: We’ve talked about the law and the changes that are good and bad. There is also the public, and this actually is the most important to me, because I didn’t come forward to tell you or anyone how they should live. I did not decide this is the way the law should be, this is the way that the law should not be.

What I saw was that the United States government was not following its own laws. It was violating the constitution and it was violating human rights. So, all I can do there or at least that I believe that I should do there is inform the public, because in a democracy, ultimately, the government is supposed to derive its legitimacy from the consent of the governed. But that consent is only meaningful if it’s informed. If we’re denied the basic facts about just the broadest outlines of the powers and policies that the government is perpetuating both in our name and that they’re then using against us in some cases, we do not control government, rather government controls us. So I went to journalists, and what this did, the impact of it is not, you know – set aside the reforms for a moment –, it is that prior to 2013 there were some academics and there were some just broadly in society, researchers, technologists, who knew these capabilities were possible, who knew this could be done, it was not unimaginable that such a system could be created, but it was unimaginable that our governments would actually apply these against people who had never been suspected of any crime. It was treated as a conspiracy theory by every major media organization. The government of course routinely denied it, which only had a more isolating effect, and this made us vulnerable to this more than decade-long gap of between what the government wanted to do, and when the public had a right or had the ability to express its feelings on the matter.

"The technological community is taking some steps to try to protect us"

So this matters quite a bit, I think, because what we suspect is very far from what we know. It is this distance between speculation and fact in a democracy that is everything, because if we cannot agree on what is happening, how can we have a conversation about what it is that we should od about it. The final outcome of 2013 is technological. When we look at, for example, the amount of encryption that happens on the internet, there is a statistic from a site 2014 where, if you look at a chart of the world’s internet communications, the level of encryption, as soon as June 2013 happened, there’s a tremendous spike in the volume of communications that no longer transit the internet electronically naked but are now protected as they traverse this hostile path. That’s only increased. Before 2013 far less than half of the world’s communications were encrypted. By 2016 it was more than half. We achieved a majority. Now, I believe, at least as measured by one of the world’s major browsers, just for web traffic, it’s more than 80 percent of these communications are now protected. This has happened in the context of messaging applications, this has happened in the context of payments, this has happened in the context of basically everything that touches technology. So we now live in a world that is more secure and more free even in the absence of greater legal reforms, because the technological community is taking some steps to try to protect us. Not all of them are doing this. Of course, there are some companies that have been really aggressive in terms of trying to stamp out privacy on the internet, because they recognize that data, the records that they can create about our lives, has been a source of money for them. But broadly, if we look at the trends, within the next few decades there will be no more unencrypted communications on the internet.

Koldehoff: So up to 2013 you also played an active role in developing the surveillance technologies that surrounded at us, at the time at least. Why did you do that at the time?

"I always believed myself a patriot"

Snowden: This is a major subject of the book, and it’s something that I struggle with still looking back through it. The primary, I think, explanation is a lack of skepticism. I was naïve. I always believed myself a patriot, I came from a family that worked for the government. My father worked for the government, my mother worked for the government, my grandfather worked for the government. As far back as you look, my people were government people. We fought in every war that the government had more or less. There is a mistake in that of just conflating support for wars with support for the country, support for government, with support for your people. But when you grow up in that environment, you take it for granted that they’re the same. So when everyone else was protesting the Iraq war, I volunteered to serve in it. I joined the army, I was in basic in training in 2004 before I was injured and put out. This is really, I think, where you can see the flaws of my ability back then to see the big picture. I would like to think that I’m a reasonably intelligent guy, but we’re all subject to emotions, we’re all subject to the propaganda that we hear, and I believed it. For me it was a question, when everyone says, oh, you know, the government is lying about this and the Iraqis have no part in this conspiracy, and there are no weapons of mass destruction, for someone like me, a young American who grew up in this kind of family, you think, well, why would they lie, why would the government be willing to sacrifice long-term trust in the very institution of government for a short-term gain in terms of political support for a war that, if the arguments are correct, is not even necessary. I was naïve, you know. It turns out the people who run my government, your government, all governments, do not always think long-term. They are very much creatures of the short-term. It was only after going deeper and deeper into government, it was only after climbing the ranks one rung, one step at a time, and it was only after going into the CIA and the NSA and working on theses systems for a very long time that I had the perspective to now look back at my life, look back at what I had done and discover that the work that I had been engaging, the work that my country’s government had been engaging was not a liberalizing force but was actually an authoritarian force, a structure of control that was not defending democracy but, in fact, unfortunately, very much placing it at risk, because when we abandon our values, we ourselves are destroying that which we claim to defend.

"I did find documents that very much shook me to the foundation"

Fries: Was there a particular moment when you decided to come out with your knowledge, to become a whistleblower?

Snowden: Well, there are, again, several moments, and this is a part of the larger narrative of permanent record. It is a process. Again, when I described where I came from, the mindset, kind of the household, the family, becoming a critic of government is the most unimaginable thing. And so people want to believe there is this cinematic moment, this aha, where, you know, you find the golden document and that’s everything. I did find documents that very much shook me to the foundation, such as the classified inspectors and generals reports on the Stellar Wind program. This is the Bush-era beginnings of the mass surveillance program that was denied to the public even after it was revealed in a scandal. It was published in December of 2005, but the press, the "New York Times", you know, the biggest newspaper in the United States, had the story right on the cusp of Bush’s reelection and they could’ve published the story, they could’ve said, president George Bush has a warrantless wiretapping program that’s violating the constitution, and even his own Department of Justice thought this was a violation of the constitution, but the publisher, Arthur Sulzberger, and the executive editor, Bill Keller, were called by the White House, by George Bush and the staff, and they said, if you run this story people will die, and they didn’t run the story, because they were afraid. They knew it was probably not true, but they, like me, were so filled with doubt and paralyzed by lack of certainty that they waited. And so George Bush was reelected by a historically small margin. That story would have meant we would have had a president John Kerry instead of president George Bush.

"I wish I could’ve said these things under the Bush administration"

This is something that I think we all miss: When you say something, it is important as what you say. If there’s any sort of criticism or self-criticism of myself that I really struggle with, it’s I wish I could’ve said this sooner. I wish I could’ve said these things under the Bush administration, even though I didn’t know about them in the Bush administration, because I believed they actually could’ve been changed. Barack Obama was such a popular president that even when he was extending and embracing some of the most troublesome, problematic of the Bush-era administration’s policies, he could more or less simply apologize and then change the drapes on the policy and they could continue. I also wonder if under a president Donald Trump we might have a larger backlash. When I came forward in 2013 I said, in recognizing this problem, that even if you trust your current system of government – and I’m not speaking about the United States here, I’m speaking in every country –, remember that you’re never more than one election away from disaster. The hands on that switch are constantly changing, and it only takes one of them to go, yes, we have prohibitions against this, yes, we’re not supposed to use this, but, you know what, we have a new emergency, we have a new threat, and now things are different, and they turn the system on, and once they do, we will have no power to resist. That is the danger of mass surveillance, is we lose the ability to organize if all our activities are known as they happen.

Koldehoff: You referred to journalism several times in your answers up till now. Having read your book, I felt that the future of independent journalism seems to worry you a lot. Why is that so and what can journalists do against that? What are you afraid of? We talked about encryption. I have to admit, I don’t know very many colleagues who use encrypted ways of communication. It’s the normal e-mail, it’s the normal WhatsApp things and so on. Is that what you mean with danger for journalism?

Snowden: Well, first off, when we talk about encrypted communications, all of you use encrypted communications, you’re just not aware of it. Every time you visit a website it has that little https at the beginning and a little lock icon, you’re using encrypted communications. If you’re using WhatsApp you’re using encrypted communications. The problem with applications like WhatsApp is, it was actually designed to have very strong encryption, just the same as the gold standard today which would be the signal messenger or the wire messenger, but then it was bought by Facebook because it was so good, and now Facebook is quite aggressively reducing the security of WhatsApp about once a quarter, and they’re trying to do it as quietly as possible, so a messenger that the people are comfortable using now is actually a danger to you. But yes, when we talk about independent journalism and threats to it, these come from many directions. I think one of the ones that we face most strongly in the United States, it’s just the growing corporatization of media. The business model of journalism seems to very much under threat when basically everything is given away for free. So they have created an advertising model and a surveillance model that they hope would work, but the people who they’re getting ads from are people like Google, people like Facebook who actually run the advertising networks. So when you look at the majority of revenues that are coming from advertising on journalism sites, some tremendous proportion of them are actually not going to the institutions of journalism at all, but rather the rent-seeking sort of ad brokers that are the very internet giants that have so hollowed out the core of the journalism industry over the last decades. So there is a structural threat to the ethics of journalism just by constructing this system of precarity. Perhaps this is not such a problem in Germany.

"What we need are not just stories but meaningful information"

Maybe there’s more public support, I don’t know as well as I do in my own country. But beyond this there is a far greater threat in terms of: you’re going to have journalism in sort of air quotes, but what we actually need is not just newspapers, what we need are not just stories but meaningful information. If journalism transforms into the production solely of stories that people want rather than the information that people need, we have lost really the fourth estate, one of the great pillars of an open society and really one of the essential structures that is necessary to retain a healthy democracy, because an uninformed public cannot cast informed votes. So this, when we look at this, what I’ve seen centrally is, the structure of the internet and the operations of surveillance, whether we’re talking about government surveillance or whether we’re talking about surveillance capitalism, and we have seen means … Sorry. What we have seen and whether we’re talking about government surveillance or we’re talking about surveillance capitalism, is a growing aggression in targeting an attempt to stamp out these sources of investigative journalism. Governments may go, we can’t get away with prosecuting a newspaper, we can’t get away with prosecuting a publisher, which unfortunately in the United States is a long-held common belief, that is coming into question with the case of Julian Assange who, like him or not, is a publisher of some of the most publicly impactful stories of the last decade, and now the government is trying to throw him into prison.

"The work of investigative journalism is very much at risk"

But moving beyond the question of Assange, when we look back just at this dynamic, investigative journalism relies upon the guarantee of the confidentiality of communications between the source and the journalist. If you cannot as a journalist convince someone working in the government, someone working in a company, that they can talk to you without facing consequences, without having their life removed, without being marched off to prison, without spending the rest of their life in exile, there are very few people who will be willing to take those risks. So the public will very quickly find itself without whistleblowers in a moment when they need them the most. This is, again, because governments now can see so much about what all of us are doing, companies can see so much about all that we’re doing, that even if Microsoft faces a leak, now they can do internal investigations and go, who amongst all of our employees using all of our systems accessed this document at this moment that was published in this newspaper, did any of them go to the website on their work computer of that journalistic outlet, and they can construct these investigations, which increasingly allow them to finger suspects and in many cases prosecute them. And so, yes, I think it is fair to say that the work of real journalism, meaningful journalism, investigative journalism is very much at risk, and if we do not do something about it, we’re going to move towards that world where we know only the entertaining news, only the non-threatening news. But sometimes to retain a free society, you have to know things that are uncomfortable, things that people do not want to be said.

Fries: And you as the president or the chairman of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, what do you suggest, what could you do, what could we do?

Snowden: Well, much of the work of the Freedom of the Press Foundation in the last few years has been to try to create technical systems that would preserve the confidentiality of source-journalist communications. This would be our platform called "Secure Drop". "Secure Drop" is a system that is run by basically every major newspaper in the world, the "New York Times", the "Washington Post", there are several, in Germany as well, where these people can connect, sources can connect through an anonymizing system – you can think of it as kind of the dark web, the Tor network – to a site that does not leave a record on the open internet if you have been there, visited it, if you do it correctly, and submit documents to this news agency without the news agency needing to even know your identity, and you can send communications back and forth over time. The journalists can send follow-up questions, they can tell you whether they’ve been able to authenticate documents, whether they need more information, and then they can publish it, and this makes it much more difficult to go after the sources.

The problem is, all of these technical methods are increasing the burden on journalists and their sources. We do not want journalists and whistleblowers to be in an arms race with the most powerful governments in the world or the biggest companies in the world, because that’s always going to be an expert battle. We’re always going to lose more fights than we win. Maybe we win enough to stay free, but we don’t want to survive, we want to thrive. For this to happen, I think, the real long-term work of the Freedom of the Press Foundation and everyone who believes in the importance of a free press is that we care and to have the public care broadly. They have to understand the value of journalism, they have to understand the threats facing journalism, and they have to have a picture of what the world will look like without people, unfortunately like Julian Assange who has many legitimate criticisms you can level against him.

But if publishers who are publishing information that, again, every major newspaper in the world has agreed is in the public interest, the "New York Times" has reported on the WikiLeaks story, the "Washington Post" has reported on WikiLeaks stories, and then they go, well, thank you very much for your work, now go to jail, we need to think about the incentives and the consequences not just in the case of Julian Assange but for every other news institution in the world. Governments, I do not believe, should have the role in society in deciding the things that can and cannot be said. I believe, these things are more properly policed, the government’s monopoly on information is more properly policed by the press itself. This is why in all of our basic laws we recognize the importance of the right to publication, of the right to speech. It will be uncomfortable, there are people who will abuse their freedoms to do harm to others, but we will mitigate those by punishing those who have caused the greatest harm, and we will hold them to the account of our laws, but we should not do so by destroying the very freedoms that those laws claim to protect.

Koldehoff: Do you think this has been clear or has become clearer after your revelations of 2013 that it’s not only a question of individuals being intercepted but also of interception structures touching the media and whole generations who are no longer protected but, as you say, well, in danger of freedom?

Snowden: Yes, I think, one of the most important things is not to lose hope. When I look around the world today, and I think when many look around it, the rising tide of authoritarianism around the world, when you see things like the AfD in Germany really gaining an alarming amount of support, you have to ask yourself, why.

I think, the answer to this is the same problem that America faced in the immediate aftermath of September 11: We are afraid. And when people are afraid, when people believe that there political opponents on any extreme are out to destroy them, if they are at risk of losing their way of life, if they’re at risk of losing their space to survive in a society, conflict and violence become attractive. The use of force becomes attractive for the government itself.

Extreme measures begin to look attractive. As we have, we experienced the constant change of political winds and one of these factions becomes empowered and they use the full strength of the government against what they believe to be their enemy, whether that’s a foreign enemy or a domestic one, we are at the real point of, I think, existential danger. This is not to say that what you face is the collapse of Germany and it’s the collapse of the United States on the map, but rather the collapse of what the society was. The flag may stay the same, the name may stay the same on the map, but the system, the values have been erased and replaced with something altogether darker.

Now, we will always face crises, we will always face conflict, and we always have, and what we need to remember is that we’re doing better now than we ever have in the past. We live in a safer world today even with the threat of terrorism, even with the violence and the crime that we see, even with the international conflict that we see today, it is nothing compared to the past. We are progressing, and so as long as we remember it is more important to persuade one another, when we understand that the answer to bad speech, to hate speech, to propaganda is in fact more speech rather than prohibitations against it, prohibitions against it, we will continue to move forward into a better time. This is critical, because, I think, when you see a lot of extreme speech and people go, we cannot permit this in our society, and I understand this is a more popular dynamic in Europe than in the United States, and there are arguments that I understand in favor of this, but look, when we talk about the most extreme positions, when we talk about the most socially harmful positions, we are also typically talking about the ones that are the easiest to discredit. These positions, this most extreme of extreme speech can in fact only survive and flourish in sheltered communities where they are not faced with opposition, where they do not have to stand on the stage before the audience and face the questions, and if through our attempts to forbid them from speaking these words we actually drive them into a dark corner, we go, yes, they’re no longer welcome in society, great, wonderful, society is more polite, but now you have a shadowed area in your country where these ideas are protected, where these ideas are mutually reinforcing, where these ideas can grow and spread and sharpen until they become viral and violent, this is what, I think, are the structural threats facing our current moment.

Koldehoff: It’s an absurd situation that a human being like you who is fighting for freedom with everything he has, namely your whole existence and that of your wife maybe as well, is not at liberty to take free decisions, you cannot travel, you’re permission to stay in Russia will end in spring 2020. Which perspective do you have and which hopes do you have concerning your personal future?

Snowden: This is one of the nice things about more or less lighting a match and setting your life on fire, is you no longer have to worry about tomorrow, because all you can do is live for the day. Tomorrow is never guaranteed for me and I cannot control it. I will not pretend to, but I also will not fear it. Again, fear is what got us into this situation. It is the response to fear. The otherizing/other rising of all these factions and recognizing the threat of it and allowing that to paralyze us with indecision or to go into a kind of bunker mentality that chills our speech, that frightens us out of acting, that has been responsible for so many of the worst decisions of the last two decades, I think, I will still be stuck in a country that I have not chosen to be in for some time, unfortunately, despite the fact that I have petition to Europe endlessly to allow me to enter.

I think, that is actually the greatest sadness of my personal story, is that what kind of example does it send into the world, what kind of an example does it send to the future, when the next whistleblower thinks that the only place where an American dissident can be heard is beyond Europe, is beyond the United States, rather than within it.

However, I do think this status quo will not last forever. Much of the reason we saw such a unreasonably shrill resistance to the revelations of mass surveillance in 2013 was, because the people in power were in many ways implicated in the creation of it. They were in many ways culpable for the violations of all the rights that followed. So while they were in power they could not risk any challenge to the structure, they couldn’t survive really the acceptance of those who exposed them as a part of polite society without risking their legacies.

Fortunately, I am a young man, and those who are in these positions are largely older and more senior in their lives, and so they will retire. I saw just yesterday a message written by someone on the internet from a very young person. This might sound a little crass, but I think it’s quite important, when you think about the most effective political argument in the United States in my adulthood has been terrorism, terrorism, terrorism.

No matter the law, no matter the topic, if you can tie it to terrorism, if you can say, your children will die, if you do not pass this law, that law will pass.

But there was a young person online, who wrote a comment, that I saw, that said, I didn’t know, what nine-eleven was until I was twelve years old, I thought it was a sex thing, like sixty-nine, because my parents wouldn’t tell me about it. There is a rising generation reaching the age of maturity now, who will not remember the trauma and fear that paralyzed us. We suffered and were victimized by a heinous crime, and what we forgot in that moment was that it was still a crime. Al-Qaida, the Taliban, terrorists around the world are not states, no matter how hard they try, no matter how well they organize, they cannot defeat our values, they cannot destroy our societies. Only we can do that. They are criminals. And if we treated them as such, and if we treat them as such, again, serious criminals but criminals nonetheless, not peers, we will survive, we will thrive, and they will be forgotten.

Fries: Under which circumstances would you go back to the US to defend yourself in court? Because you said, you seem more confident now, because some allegations would not come up again. Why do you think, why do you have some hope?

Snowden: When we look back at what happened in 2013, the government had been exposed for breaking the law in the United States, and their immediate response was: revealing that we were breaking the law is itself a crime, and they charged me with three very serious felonies related to the provision of information to journalists.

The interesting thing about this law, that they charged me under, is, that it forbids any defendant from arguing to the jury or even mentioning in the court room why it is that they did what they did and to have the jury decide, was this justified or not justified. The government forbids this under the espionage act of 1918.

It’s funny it’s called the espionage act, that under Barack Obama it was used more times against the sources of journalists rather than the sources of foreign intelligence, more times than all other presidents combined. I think, the current president, if he is reelected, will very much try to break that record, and I fear that this will be a growing bipartisan trend.

But despite that, despite the fact that the government believes every document, that is classified, that the public learns of through journalists, is a felony, telling the truth to a journalist is a crime, that will result in a sentence of ten years per document, which in my case now it would mean I’d spend the rest of my life and the rest of all of our children’s lives in jail.

Despite that I have said I would happily go back to face a trial, if the government will permit that public-interest defence, if the jury can hear, what I did, if the jury can hear, why I did it, and if the jury can make a decision, of whether this was justified or unjustified, I’ll be back.

Unfortunately, the United States government from no less than the attorney general responded and said, we won’t do that. What we will provide instead, our counter-offer is a written guarantee, that we will not torture you. It is my position, that is not enough! It’s also one last interesting point of history, that same attorney general, Eric Holder, who in 2013 charged me with all of these felonies, after he retired as an attorney general said himself, he’s on the record saying this, that he believes, what I did was a public service. If that is the case, why can I not come home?

Koldehoff: With regard to your future and your wife’s future, what expectations, what wishes do you have concerning Germany? Is there something like a message to the German government?

Snowden: I think, this is always the question, where people want to hear me, say, you know, please, please let me in. I have been clear from the very first day, that I left Hongkong and was trapped in the airport for 40 days in Russia and applied for asylum in 27 different countries around the world, yes, please, allow me into Europe, because one of the only political attacks that the United States government still repeats against me, because all of their other claims have fallen apart, is that, well, no matter, what you think of the man, he’s in Russia, and Russia has a poor position on human rights, and they’re correct.

They don’t tell people, they’re the ones who trapped me in Russia, they do not tell people, that Germany, France, Europe will not permit me to enter their country. But I would say to Europeans, it’s not a question of what happens to me. What happens to me is no longer important. What is important is, what happens to the next whistleblower, and if you allow them to believe, that they will no longer be free, that they will be trapped in exile for the rest of their life in countries, that they could not choose, that is not … This is not about me. It is about us, and it is about the message that we want to send to the future.

Koldehoff: There are already some reactions to interviews which you gave within the last days from German politicians, support from the social democrats as well from the green and the left party, refusal from the CDU with statements like, he would get a fair constitutional trial in the US or disclosure of state secret is a crime all over the world, did they understand what you wanted and what you did?

Snowden: I think, from the CDU, this is a fairly classic position. Their most famous position is not to take a position. I think, it’s a little bit sad, and I think, the journalists, when they put these questions to these officials in the CDU, they need to follow up, and they need to say, you understand correct, that he would not be afforded a public-interest defence, you understand correct, that he would be forbidden from having the jury decide, that this was justified or unjustified. I am not facing prosecution in the United States under current laws. Prosecution implies a fair trial, and a fair trial is forbidden, because of the lack of access to a public-interest defence. It is forbidden by law. That is not a prosecution. That is persecution. We have had the EU parliament pass resolutions that say, whistleblowers – and it cites me by name – should be protected in Europe. The question is, why do we only see these certain parties really trying to bend backwards to demonstrate loyalty to a president, who considers them an enemy.

Koldehoff: If Germany is one of your options, you’re still aware of the fact that there are no Taco Bell restaurants in Germany?

Snowden: As I said, we have come out of dark times in history, and I believe, someday Germany will progress to a future with Taco Bell in time!

Koldehoff: We did not discuss the question whether you’re a Russian agent. Can we leave that, is that okay for you if we don’t discuss that again?

Snowden: It’s fine! I think it’s been endlessly covered. If you want to, you’re more than welcome to, but, yes, that answer is, I think, well-established!

Koldehoff: Okay!

Fries: Thank you very much for your time, for joining us!

Snowden: Thank you very much for having me!

Koldehoff: Take care!

Äußerungen unserer Gesprächspartner geben deren eigene Auffassungen wieder. Der Deutschlandfunk macht sich Äußerungen seiner Gesprächspartner in Interviews und Diskussionen nicht zu eigen.